At a point in the game, you say to yourself “Stockfish ought to take a few lessons from me”. You just made a beautiful tactical maneuver that would’ve made Emanuel Lasker applaud. Now you have a significant lead in the game, and you just can’t help but sit back and pummel your opponent. In a twinkle of an eye, you realize that you’ve squandered your advantage and parity has been restored in the game. You sit up. No more games—time to unleash some of that sweet magic once more. It’s a King and pawn endgame, and you know your instinct will be your guardian angel as usual. You’re irritated to see a draw-ish position.

Now things are about to get much worse as you realize that you’re down a crucial tempo. A few exchanges here and there, and your opponent has a passed pawn. A strong tension headache caresses your occipital as you realize your loss in this game—a game you already had in the bag. Now, I’m going to make sure you leave less of the outcomes of your endgames to fate. Follow carefully as I unveil important but underrated theories of the endgame.

Zugzwang

Firstly, we must understand what this term means. This move indicates that a helpless move MUST be made by the side with the next turn. The move will be disadvantageous—no matter what piece is played and how it is played. Zugzwang is arguably the most lethal weapon of the endgame. Tempo is as precious as gold, as one misplaced move could cost the game.

Key square

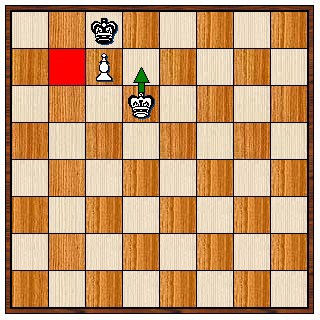

A key square is any square that, once occupied by a King, offers major advantages to any side. Key squares are common in the endgame, especially with just the King and pawns left. A King on a key square could perform defensive duties by guarding its pawn to promote, or it could perform attacking duties by capturing opposing pawns or acting as a blockade against promotion.

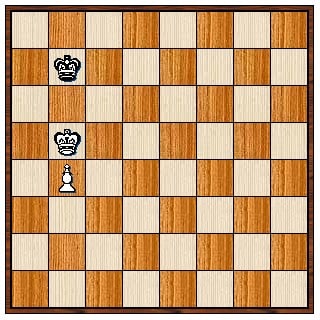

Below is an illustration of a key square.

Corresponding squares

Some would describe the concept as the law of “sister squares”. The word “sister” indicates close likeness. This rule simply explains the mechanism of King’s movements in a tight end game. The rule of corresponding squares, if followed in a King and pawn endgame, can salvage the game for a side that is down material. The defending king blocks all routes leading to squares that could cost the game.

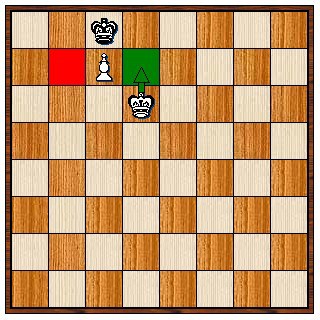

We illustrate this narration in the position below

From the image above, d4, e3, and e2 are key squares.

This rule of corresponding squares is not exclusive to defending as it also applies to winning a narrow game. Having a firm knowledge of the rule of corresponding squares gives one an edge when the need to apply the rule looms. The player prepares for the rule and quickly navigates it in their favor.

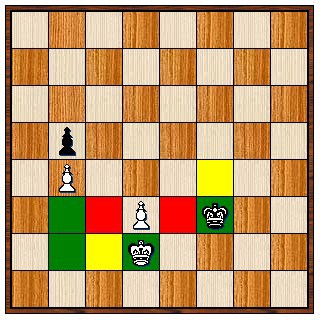

Furthermore, when there is only a pair of corresponding squares, this is called MINED SQUARES. The word “mine” refers to the hidden explosives used in conflicts. Similarly, mined squares in chess simply mean that moving the King to that square, before the opponent does, would be catastrophic. Therefore, both players must avoid playing to mined squares in order not to be Zugzwang-ed.

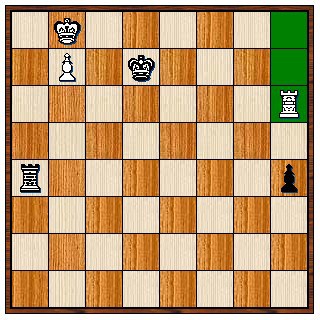

Mine squares are illustrated in the image below

Triangulation

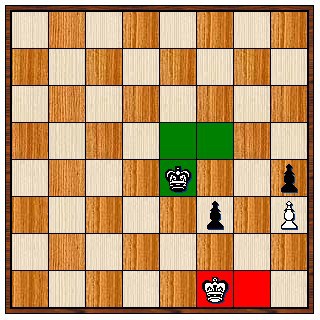

This concept appears to be the disequilibrium version of the corresponding squares. As the name implies, a player moves the piece around three close squares. These three squares form a triangular shape, hence the word, “TRIANGULATION”. Once again, triangulation is powered by the lethal endgame weapon, Zugzwang. The essence of triangulation is to win a tempo and seize control of the game. A player can only practice this tactic when his King has more “free squares” than his opponent’s king.

Take note that triangulation is not a tactic exclusive to the king alone. Other pieces on the board, such as the rook and queen, can also use the tactic. You might be wondering how a Rook can be able to move in a triangle. Well, this is the only exception to the term “triangulation” in chess.

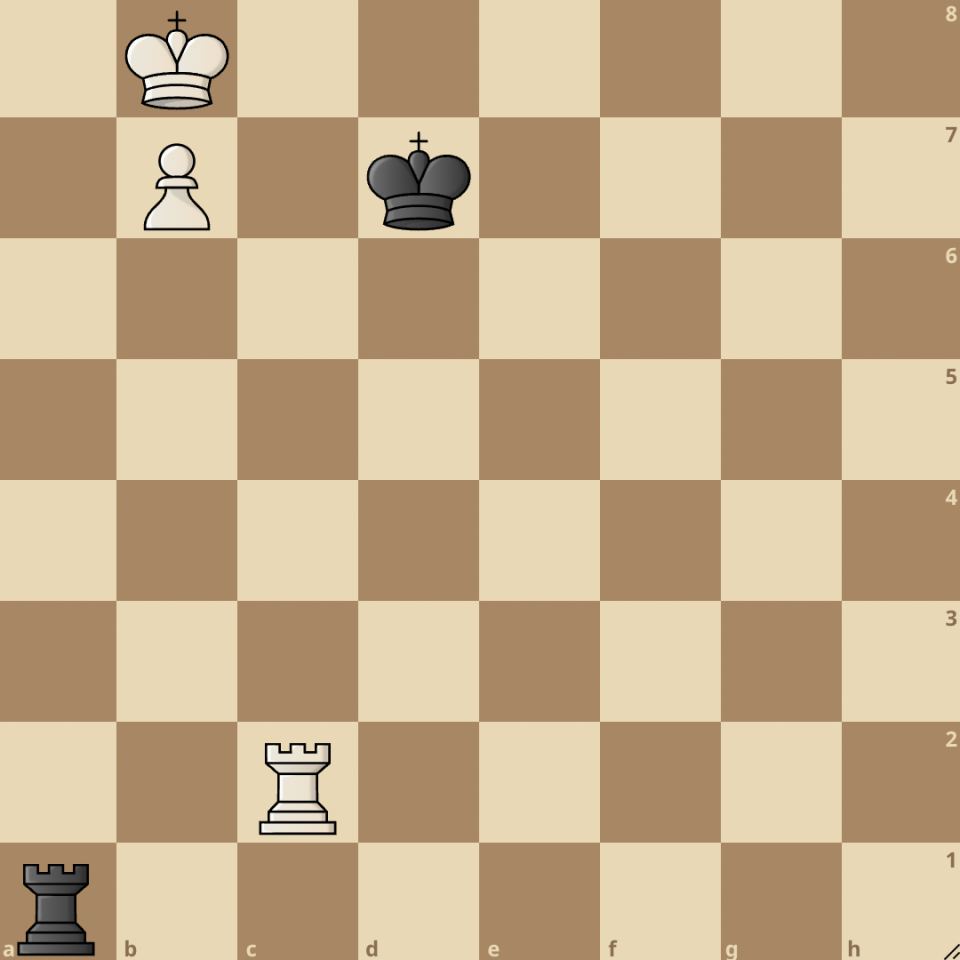

The rule of triangulation with the king is explained with the image below

The rule of triangulation with the rook is illustrated in the image below.

After triangulation, the original position is recreated, but this time it’s Black’s turn to move.

Opposition

The game of chess is all about conquering the opposition but rarely do we ever see the Kings of both sides directly oppose each other. This tactic, once more, refers to our powerful endgame weapon, the Zugzwang. For this tactic to be executed, both Kings must be on the same file or rank, except in unusual cases of diagonal opposition. All other pieces must be in a blockade. In this case, the side to move enters into a Zugzwang situation.

Once the King moves from its square, the opposition tactic has been successfully executed, and the next player to move will have a major advantage. This tactic is similar to the rule of corresponding squares, but it is more like when the rule goes wrong for either side.

The image below sheds more light on this endgame tactic.

Many speculate that Magnus Carlsen’s understanding of the endgame is the reason why he is dominant. If this theory is correct, and it very likely is, every player should take the endgame more seriously. More often than not, chess games played at the top level reach the endgame. Therefore, the best understanding of this phase is the only way to assure the best result. A player who knows a good opening repertoire, a truckload of tactics, and middle game strategies but lacks endgame knowledge might struggle to become a top player.

join the conversation