Introduction

Chess is categorized into three phases; the opening, the middlegame, and the endgame. The phases are identified to enable theoreticians to study chess more effectively.

The chess opening is where each side sets up its pieces in preparation for an attack on its enemy.

The middle game phase is where the majority of chess tactics are put to use. And the chess endgame, the phase with a few pieces left, is highly critical and complex.

Therefore, in detail, let’s look at a chess endgame.

What is a Chess Endgame?

The chess endgame is the twilight of a chess game because just a small fraction of the pieces that started the game remain.

Fourth World Chess Champion Alexander Alekhine said, “We cannot precisely define when the middle game ends and when the endgame starts.”

Similarly, the scarcity of the pieces on the board leaves a small error margin leading to claims that the endgame is the most critical phase of a chess game.

These claims are not unfounded, as the endgame crowns the efforts from the opening and the middlegame.

Max Euwe and Walter Meiden Endgame Considerations

- A player has a 90 percent winning chance with an extra pawn in king and pawn endings.

- In an endgame with pieces and pawns, an extra pawn gives a 50-60 percent winning chance.

- The king becomes the most important fighter.

- The initiative is more important in the endgame than in other stages of a chess game.

- Connected pawns increase winning chances significantly. The longer they are, the better the winning chances.

Common Chess Endgame Principles

To play the chess endgame effectively, one must take note of these key chess terms and concepts:

- The Square Rule

- Key Squares

- Opposition

- Zugzwang

- Pawn Structure

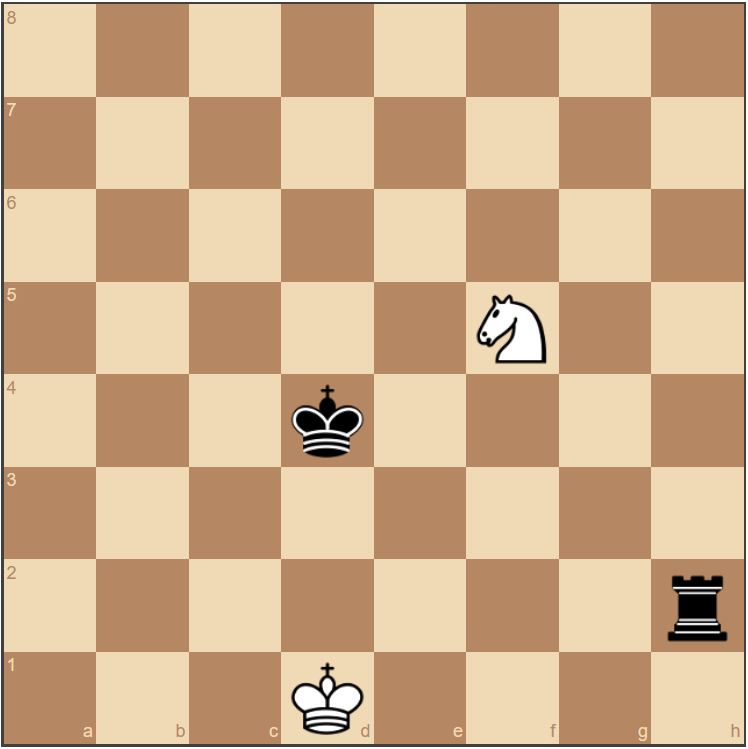

The Square Rule

The Square Rule states that the king can catch the pawn if it can step into the “larger” square on its next move.

For context, a larger square is any dimension on the chessboard excluding a lone square such as the a5-square, b2-square, h6-square, etc. larger squares on the chessboard measure from a 2-by-2 dimension to, of course, an 8-by-8 dimension.

Although this rule requires a square structure, ranks are more relevant here than files.

By the same token, if the black king sits on c4 and a white pawn sits on g4, regardless of whose turn it is, the black king will reach the pawn before it promotes on g8.

All the king has to do is travel diagonally as the pawn travels vertically forward.

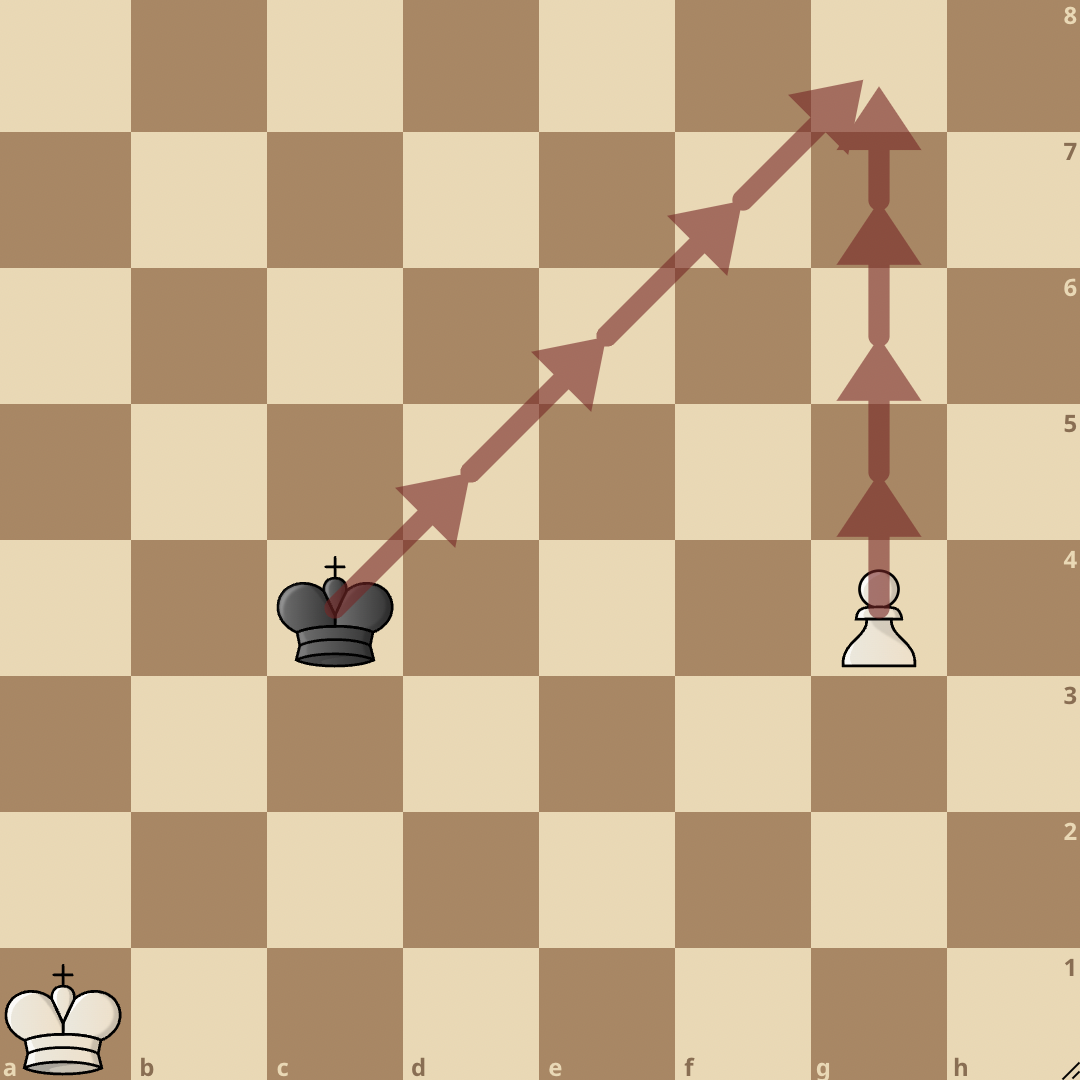

Key Squares

A key square is any square in the endgame to be occupied by a king to protect or attack for a gain in advantage.

If you’ve ever promoted a pawn by placing your king on the 7th rank, you have used the rule of Key Squares.

Similarly, if you’ve ever prevented a pawn from being promoted by occupying the 7th rank, you have also used the rule of Key Squares.

This rule is most common in king and pawn endgames, and some positions have both white and black key squares.

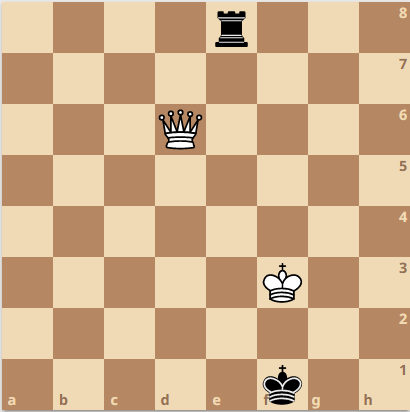

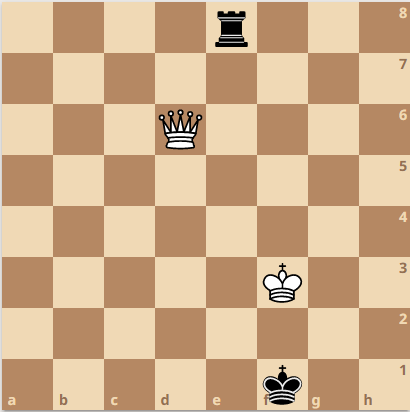

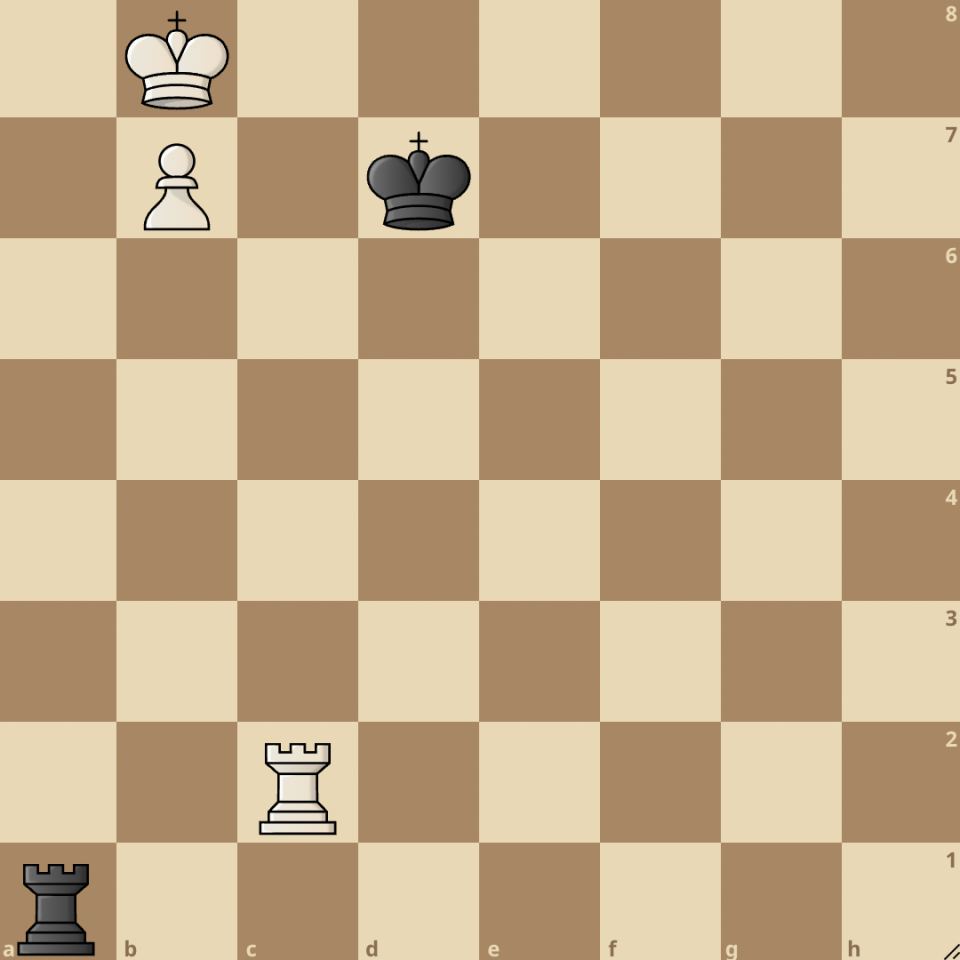

See an example below:

In the position above, White can win if he decides to take control of the key squares g7 and g8 to promote the h- pawn. If White allows Black to occupy those squares, the game goes from a simple win to a draw.

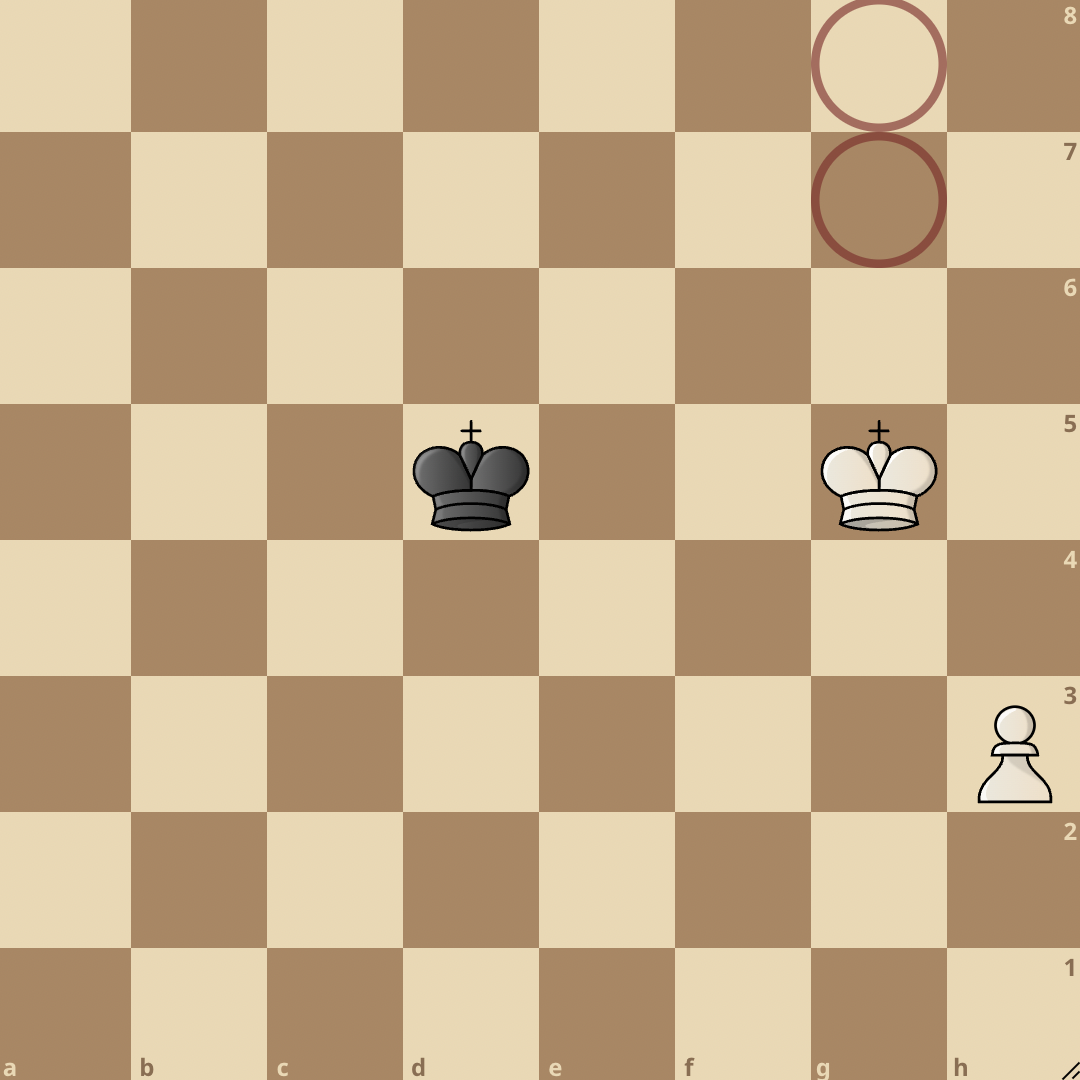

Opposition

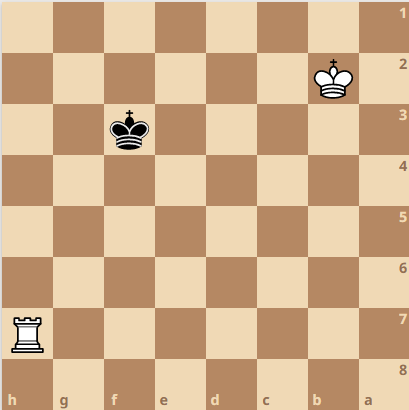

Opposition is having two kings sitting two squares apart from each other on the same rank or file. This illustration is also called Direct Opposition.

Opposition is powered by the chess piece rule that states that kings cannot sit a square next to each other. Sometimes, Opposition occurs diagonally, which is also called Diagonal Opposition.

If the white king is on f6 and the black king is on f8, the black king has been opposed successfully. This term is affiliated with restricting flight squares of a king under attack.

Opposition often puts a king under Zugzwang.

Zugzwang

This German word can be translated to “The compulsion to move.” Therefore, whether the move is favorable or not, one must move.

In chess, Zugzwang often refers to an unfavorable move, but the player doesn’t have a choice. So, in chess endgames, this concept is extremely useful because moves become limited.

Zugzwang, Key Squares, and Opposition concepts rely on another chess concept called Tempo.

Pawn Structure

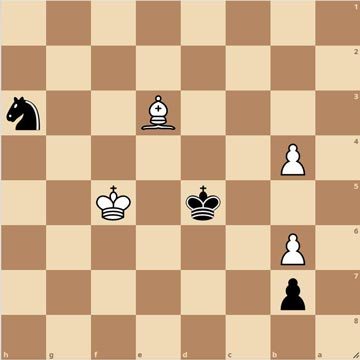

Divided, they are weak, and together, they are unimaginably strong. Hence, we must try to keep pawns together at every stage of the game because, at the endgame, these united pawns manifest their full glory.

For this reason, pawn structures are studied, and theories are discovered to help us play chess better. In addition to having a well-connected pawn structure, we must also remember to avoid having lone pawns, doubled pawns, and sometimes tripled pawns.

And we must look to create passed pawns for a significant endgame advantage.

Types of Chess Endgames

Chess Endgames come in different types because all the types of chess pieces cannot be present in the endgame.

Only a selected few must be present; these few can be any piece. Since there are six types of chess pieces(king, queen, rook, knight, bishop, pawn), in which one piece must be constant in the endgame(the king), we are left with multiple possible outcomes.

The endgame could have two, three, and sometimes four types of pieces. For instance, an endgame with just rooks left must be studied differently from an endgame with minor pieces and pawns left. This demonstration is why chess endgames are listed to the types listed below:

- No Pawn Endings

- King and Pawn Endings

- Knight and Pawn Endings

- Bishop and Pawn Endings

- Rook and Pawn Endings

- Queen and Pawn Endings

- Rook Versus A Minor Piece

- Two Minor Pieces Versus A Rook

- Queen Versus Two Rooks

- Queen Versus Rook and Minor Piece

- Queen Versus Rook

- Piece Versus Pawns

No Pawn Endings

No Pawn Endings refer to any endgame without the presence of pawns. Usually, all the pawns in the game have either been captured or promoted.

Pawn Endings correspond with the Four Basic Checkmates. Aside from the Four Basic Checkmate instance, where a side has an overwhelming advantage, No Pawn Endings are likely to end as a draw.

This outcome is because there are no pawns to give any side hope of promoting a powerful piece that could decide the game.

King and Pawn Endings

There are no other pieces on the board but kings and pawns, regardless of the number of pawns left. A King and a lone pawn endgame will likely end as a draw, depending on key squares.

Knight and Pawn Endings

Some say knights are good blockaders, but when chasing down a passed pawn, knights are not efficient. If there is a lone pawn in the game and a knight on each side, the losing side must do all to capture the pawn to seal a draw.

Bishop and Pawn Endings

Since bishops move diagonally, pawns are placed on squares the bishop cannot occupy. For instance, if white has just a light-squared bishop left, black must try to place all their pawns on dark squares.

When both sides have a bishop, each left and these bishops play on opposite squares; the game is likely to end as a draw depending on the number of pawns present and the position of the king.

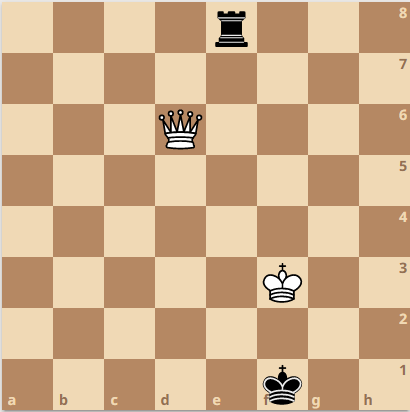

Rook and Pawn Endings

This type is one of the most common endgames that leads to several theories a masterful player must know. One major rule in rook and pawn ending is the Tarrasch Rule. This rule states that players must place rooks behind either ally pawns or enemy pawns.

In these chess endgame types, it is important to note that rooks are more effective as attackers than defenders. Therefore, having rooks on the seventh rank is an important rule of thumb in the endgame.

Queen and Pawn Endings

In most cases, a queen can stop the promotion of even connected pawns as long as the enemy pawns don’t have a queen ally. In a scenario where both sides have a queen and an equal number of pawns, the game will likely end as a draw.

Rook Versus A Minor Piece

These positions can either have pawns or not. Most times, the pawn difference between the sides determines who wins. But in a position whereby each side has no pawns, the side with the rook could win, but the game is more likely to end in a draw.

Two Minor Pieces Versus A Rook

Once again, pawns’ presence and structure often define chess endgames like this. In a case of equal pawn numbers and structures, the two minor pieces are more likely to win, especially if they are a bishop pair.

Queen Versus Two Rooks

In the chess endgame, two tools match the power of a queen in certain positions, provided both rooks are connected. This endgame often ends in a draw unless there’s a deciding factor like an extra pawn for either side.

Queen Versus Rook And Minor Piece

In the endgame, it will be extremely difficult for a queen to overpower a rook and a minor piece, especially a knight. If there are no pawns, the queen is likely to win.

Queen Versus Rook

Connected pawns are the only assets that can give a side with a lone rook a win against a queen. The rook, protected by the king, obeys the Tarrasch Rule while the queen looks for check forks. Without pawns, the rook usually stands no chance against the queen in the endgame, but a draw is still possible—rare but possible.

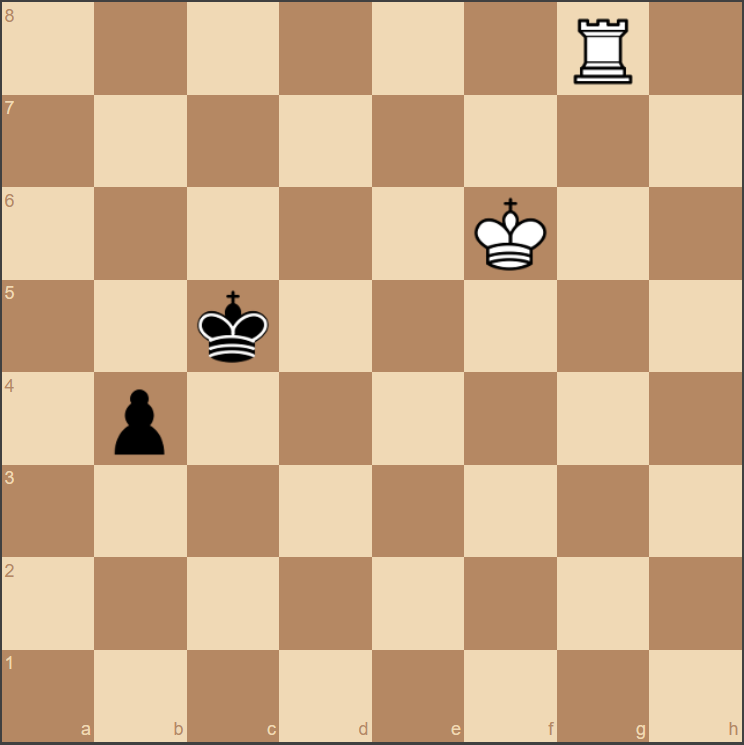

Piece Versus Pawns

This type of endgame occurs more often than many other types of chess endgames. If the pawns are connected and advanced considerably, the side with pawns stands a chance, provided the enemy king is positioned far from the pawns.

Top 10 Chess Endgames You’re Most Likely To See In Your Games

10. Rook and Bishop Versus Rook (1.77%)

9. Queen Versus Queen (1.87%)

8. Rook and Bishop Versus Rook and Opposite-colored Bishop (1.92%)

7. King and Pawns Versus King, sometimes with Pawns (2.87%)

6. Rook and Knight Versus Rook and Knight (3.09%)

5. Bishop Versus Knight (3.29%)

4. Rook and Bishop Versus Rook and Same-colored Bishop (3.37%)

3. Two rooks Versus Two Rooks (3.45%)

2. Rook and bishop Versus Rook and Knight (6.76%)

1.Rook Versus Rook (8.45%)

Note that pawns could accompany any piece on either side of the endgames.

Chess Endgame categories

The chess endgame has three subcategories, namely:

- Practical endgames

- Theoretical endgames

- Artistic endgames

Practical Endgames

These endgame categories are extracted from games played in real time. Hence, it ought to result in a theoretical endgame when played correctly.

Theoretical Endgames

Theoretical endgames are defined endgame positions that can be maneuvered through without further complications when recognized in a practical endgame. Theoretical endgames can either lead to a dead draw or a clear win/loss.

Therefore, when next you see a player resign earlier than expected in an endgame, it is likely because they recognized the theoretical endgame they got submerged in, which wasn’t favorable.

Examples of some theoretical endgames include;

- Lucena position

- Philidor position

- The Kling and Horwitz Defense

- The Vancura Defense

- The Cochrane Defense

- Distant Checks Position

Lucena Position

The Lucena Position is one of the most famous concepts in Endgame theory. It is coined from the Rook and Rook endgame. More precisely, a side has a pawn already on the brink of promotion. In comparison, the losing side battles with his king and rook to prevent the seventh-rank pawn from reaching promotion.

Once in the Lucena Position, the side with the pawn wins with accurate play. In the position, both enemy rooks will be on files that help them control both the movement of the kings and the type of pawn. The winning king is placed in the promotion square of the pawn on the seventh rank.

The enemy rook, several ranks away, ensures that the king doesn’t give way for the pawn to be promoted, while the enemy king also restricts the winning king’s flight squares.

Philidor Position

This position is also a rook versus rook endgame. In contrast with the Lucena Position, the Philidor position assures a draw. Although the materials are identical to the Lucena position (Two kings, two rooks, and a pawn), the Philidor position doesn’t count the extra pawn as an advantage.

Once more, in contrast with rooks in the Lucena Position, the rooks in the Philidor Position operate via the ranks (not the files). Furthermore, one can identify the Philidor Position when:

- The defending king is placed on the advancing pawn’s back rank and promotion square.

- The attacking king is outside three ranks of the defending king.

- The pawn is not within three ranks of the defending king.

- The defending rook stays two ranks from the king to prevent the attacking king from advancing past that point.

If the attacking side advances the pawn beyond the fourth rank, the defending rook moves to the opposite back rank to deliver perpetual checks or force the king to abandon its protection.

The Kling And Horwitz Defense

This chess endgame study dates back to 1851. This position is the final resort for a game that couldn’t reach the Philidor Position successfully. In the Kling-Horwitz Defense, the attacking king is not behind or around the pawn but in front of it. The defending rook then sits behind the pawn. Also, the rook occupies the promotion square of the knight, while the defending king sits close to the attacking king and the rook.

The Vancura Defense

Players rated below 1800 are prone to blundering this position and losing the game even when it’s a theoretical draw for the seemingly losing side. Like the Lucena and Philidor Positions, the Vancura Defense occurs in the Rook and Rook endgame. This position must occur with the pawn on the extreme file (a or h) and the attacking rook placed on its promotion square.

Both kings are distant from the pawn, but the attacking king joins the battle to help the pawn get promoted. Meanwhile, the defending rook is stationed behind the pawn. The pawn gets captured if the attacking rook leaves the back rank square where the pawn is meant to promote.

We recall that the defending king is far away from the action. This choice is best because, in a bid to help out the situation at one end of the board, the defending king could plunge his side into irreparable turmoil. The Vancura Defense defends that the defending king is placed on the back rank on either the b-file (black king) or g-file (white king).

If the king moves to the c-file, regardless of whether it’s on the seventh rank, the defending side loses. The reason is that the attacking rook will leave the pawn’s promoting square to the other edge of the board. The pawn gets promoted if the defending king returns to its initial square on the b or g-file. If the defending rook captures the pawn, we have a seventh check on the h or a-file and a skewer tactic by the attacking rook.

The Cochrane Defense

Finally, we’re no longer looking at a theoretical chess endgame position from the Rook Versus Rook endgame. The Cochrane Defense, named after John Cochrane, is a draw position from the Rook and Bishop Versus Rook endgame. Sometimes, it can also emerge from the Rook and Knight versus Rook endgame.

Thanks to the absence of pawns, the losing side is presented with a chance to salvage the game. The following factors are considered in the Cochrane Defense;

- The minor piece must be pinned to the king by the defending rook.

- The defending king must be at least three ranks away from the attacking king.

- The pin must occur in the board’s middle four files (c, d, e, and f).

- In most cases, the attacking rook restricts the defending king to his back rank. And the attacking side must be careful not to trade off rooks because that would seal the draw instantly.

Distant Checks Position

This endgame position usually occurs in the Rook Versus Rook chess endgame. The king blockades the pawn while the defending rook finds the safest distance to deliver checks to the attacking king.

The attacking rook must always protect the pawn lest the king captures it. Therefore, to keep the pawn protected, the defending side delivers checks from a safe distance until the game is drawn.

More theoretical endgame positions are embedded in a “100 Endgames You Must Know” book by Jesus de la Villa. You can also get great chess books for beginner and intermediate levels here.

Quotes on the Chess Endgame

-In the ending, the king is a powerful piece for assisting his pawns or stopping the adverse pawns.

Wilhelm Steinitz

The best way to learn endings, as well as openings, is from the games of the masters.

Jose Capablanca

After a bad opening, there is hope for the middle game. After a bad middle game, there is hope for the endgame. But once you are in the endgame, the moment of truth has arrived.

Edmar Mednis

The business of the endgame is maneuvring to control critical squares, advancing or blockading passed pawns, preparing a breakthrough by the king, or exploiting the subtle superiority of one piece over another.

Pal Benko

To improve at chess, you should, in the first instance, study the endgame.

Jose Capablanca

Conclusion on Chess Endgames

Despite having a few pieces left on the board, chess endgame theory is broader and more complicated than chess opening theory. This understanding is why chess coaches advise their students to spend 20% of their time studying the opening, another 40% studying the middle game, and the final 40% studying the endgame. This recommendation is called the 20/40/40 rule.

We’re all aware of the popular life quote by Jim George, “it’s not how you start that’s important, it’s how you finish!”. Therefore, we must all learn chess games to a good degree to attain our desired level of mastery.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is a chess endgame?

A chess endgame is the final phase of a chess game, when there are only a few pieces left on the board. In contrast to the opening and middlegame, the endgame is focused on positioning the remaining pieces in a way that gives you a winning advantage. Common endgame strategies include promoting pawns to queens, using the king to attack your opponent’s pawns or pieces, and using the rook to control open files or create a passed pawn.

How is a chess endgame different from the opening and middlegame?

During the opening and middlegame, the focus is on setting up positions and making tactical moves. The endgame, on the other hand, is all about using the remaining pieces to your advantage and trying to outmaneuver your opponent. While the opening and middlegame involve a lot of back and forth, the endgame is often more about careful calculation and planning.

How can I improve my endgame skills?

If you want to improve your endgame skills, there are a few things you can do. First, study endgame positions and tactics. This can include reading books, watching videos, or using online resources. You can also practice endgame positions with a chess engine or by solving chess puzzles. Finally, be sure to analyze your own endgame play to identify any weaknesses and areas for improvement.

Are endgames always easy to recognize?

Not necessarily. Some endgame positions may resemble middlegame positions, so it’s important to be careful and consider the relative value of the pieces on the board. Keep an eye out for opportunities for pawn promotion and other endgame strategies, and make sure to analyze the position carefully before making a move.

How do I know when a chess game has reached the endgame?

A chess game is generally considered to have reached the endgame when there are only a few pieces left on the board. This usually happens when most of the pawns have been captured or have reached the other side of the board, and when there are only a few major pieces (queens, rooks, and bishops) remaining. However, it’s worth noting that some chess games may reach the endgame much earlier, especially if one player has a significant material advantage.

What are some common mistakes to avoid in the endgame?

One common mistake in the endgame is to not pay enough attention to the position of your pieces. Make sure to keep your pieces coordinated and try to control key squares or lines of attack. Another mistake is to neglect the importance of your pawns. Pawns may not be as powerful as other pieces, but they can be crucial in the endgame, especially if they are able to promote to queens. Finally, be sure to watch out for stalemate, where neither player can make a legal move but the game is not won.

How important is it to study endgames?

While it’s important to study all aspects of chess, the endgame is often considered one of the most important phases of the game. This is because endgames often involve a limited number of pieces and more precise calculations, and a player’s endgame technique can often make the difference between winning and losing. As such, it’s a good idea to spend some time studying endgame positions and tactics in order to improve your overall chess skills.

Are endgames always decisive?

Not necessarily. While many endgames do result in a win or a draw, it’s possible for a chess game to reach a position where neither player can make a decisive move. In these cases, the game may be declared a draw. It’s also worth noting that some endgames may be drawn even if one player has a material advantage, if the player with the advantage is unable to make progress.

join the conversation