An exchange sacrifice is a chess move where a player trades their rook for the opponent’s bishop or knight.

This move is usually made for strategic or tactical reasons, such as gaining control of open files, initiating a mating sequence or dominating weak squares in the opponent’s camp.

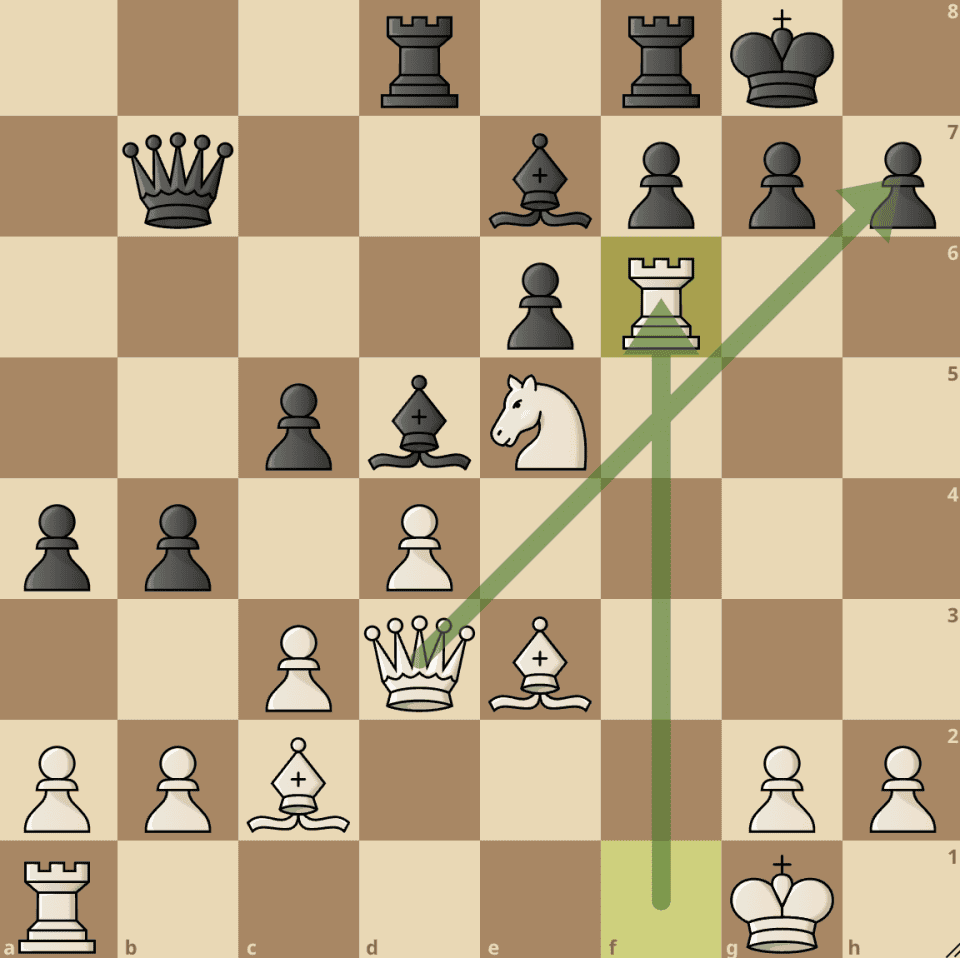

Take a look at the position below:

Black was far better in this position but made a blunder by playing Qb7 possibly targeting the pawn on g2.

White sees this threat but has something better. The position of the White queen and bishop battery breathing fire on the b1-h7 diagonal allows for this tactical shot.

White can immediately play Rxf6! taking out the only defender of the h7 pawn.

Black can’t capture with either the pawn or dark-squared bishop as that’ll be mate on the next move. So he’s forced to play something like …Be4 stopping the attack. A move like …g6 will only fuel the attack after Nxg6! In any case, Black is losing.

This is the point of the exchange sacrifice – to tilt the game either tactically or positionally. We’ll see a positional example in the next section.

Why Play The Exchange Sacrifice?

You can play the exchange sac to destroy your opponent’s pawn structure. The motivation for this can be tactical or strategic.

For instance (just like the position we already discussed), if White has a rook on an open f-file and Black’s king has castled, and Black has a knight on the f6 square with no piece supporting this knight, most players would not hesitate to play Rxf6, destroying the pawn structure.

Black would have to recapture with gxf6, exposing the king to further danger. This kind of idea is also common in the Sicilian defense, where Black plays Rc8xNc3.

See this game that was played by former world champion and legend, Garry Kasparov. It featured a RxN exchange sacrifice to give his opponent double pawns and a weakened king which he fully converted about 19 moves later.

Click the moves or move the board around for a better interactive experience

Other reasons to play the exchange sac include:

- To establish a minor piece on a strong square. White can sacrifice their rook to gain total control over an important square in the opponent’s territory.

- To dominate weak squares in the opponent’s camp.

- To gain a lead in development.

- To achieve connected passed pawns.

The exchange sacrifice is commonly played by experts and masters, as most beginners and intermediate players have difficulties parting with material. Moreover, it would be difficult for them to exploit the positional advantages brought about by the exchange sacrifice.

The exchange sacrifice was one of the trademark resources of Tigran Petrosian, the ninth world chess champion. He was known for his ultra-solid and defensive style of playing, which earned him the nickname “Iron Tigran”.

He brought about a new look to exchange sacrifices. He knew how to steer the position in a way that would favor him by making use of the accumulated positional or tactical advantages.

Below is one of his games against Samuel Reshevsky in the 1953 candidates tournament.

Petrosian was playing with the Black pieces in this game. In the position, Black appears cramped while White pieces are poised for action except the b2-bishop which looks more like a tall pawn.

If White is allowed to play Bf3 and d5, then Black would be doomed. Petrosian saw these possibilities and deduced that the Black knight would be better placed on the d5 square blockading the White pawns, attacking the c3 pawn, and supporting a potential b5-b4 pawn break.

The knight can easily be transferred to the d5 square through the e7 square, however any move such as Ra7 or Rc7 making way for the knight would punished by e6!

Petrosian however finds a subtle way to achieve this maneuver.

25… Re6!!

Black willingly offers an exchange sacrifice. After 26. Bxe6 fxe6, Black will have adequate compensation as the knight can now sit comfortably on the d5 square.

26. a4?! White sets up a little trap

26…Ne7!

(26… b4?! is inaccurate as white can go 27. d5! Rxd5 28. Bxe6 fxe6 29. Qxc4 and the position is open in White’s favour)

27. Bxe6 fxe6 28. Qf1 Nd5

White was forced to give back the exchange two moves later and the game ended in a draw 13 moves later.

Check out the full game below:

That’s one good example but here’s another.

Tigran Petrosian was Black playing against Lev Polugaevsky in Moscow, 1983.

In the position above, it’s clear that White has some pressure on Black’s queenside – on the b6 square and the b7 pawn while Black has eyes on the weak c4 pawn and seeks to exploit the weak c5 square.

White’s dark-squared bishop displays radiance holding White’s position together and pressuring the weak dark squares in Black’s position.

Petrosian decides to take this valuable bishop after concluding that the bishop was better than his rook at e8.

19…Rxe3!

20. fxe3 Nc5!

Black now establishes his knight on the c5 square protecting the b7 pawn and clamping down on the e4 pawn. The absence of the bishop makes this possible and makes the new e3 pawn weakness a target for the Black rook. The bishop on g7 can also attack the pawn from h6.

4 moves later, Polugaevsky resigned after a blunder where Black’s knight was able to fork the White queen and one of the rooks. We suspect that the unexpected exchange sacrifice had a psychological effect on Polugaevsky.

Check out the full game below:

So, we see that the exchange sacrifice is a very useful tool that can be very dangerous in the hands of a master. It also brings out creativity in a game and it’s fun to play.

Ever played an exchange sacrifice before? What happened in the game thereafter? We’ll love to hear you!

1 comment

zidane

very good information. thank you