After watching the award-winning movie ‘Searching For Bobby Fischer’, a lot of people ask this familiar question: “Does Josh Waitzkin still play chess?”

He was believed to be the ‘next Bobby Fischer’ in the United States, as he had already obtained an IM title as one of the youngest at that time.

A lot of people looked up to him, as he was really popular then, all thanks to being the main character of the book and movie “Searching for Bobby Fischer”.

But now, it appears things have gone awry but that still leaves the question “Who is Josh Waitzkin and does he still play chess?”.

Let’s have a look at Josh and his early days as a chess player.

Who is Josh Waitzkin?

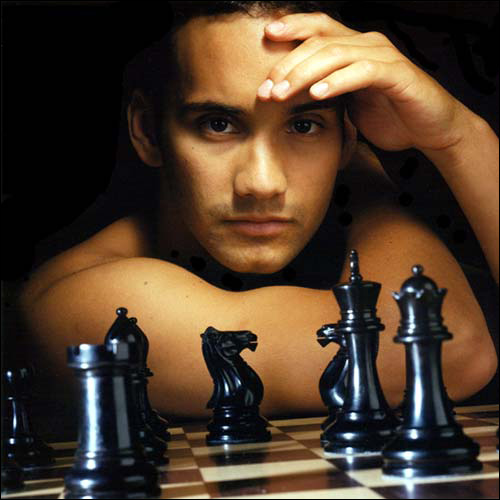

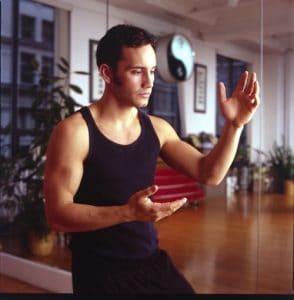

Josh (short for Joshua) Waitzkin is a chess player and martial arts practitioner that was born on December 4, 1976. He’s also an author, having written a number of books and is from the United States.

Josh Waitzkin And His Early Chess Career

Josh was not like any other ‘normal’ kid when he was little. He was regarded as a chess prodigy, a young one who excels at the game of chess well beyond what one could expect for his age.

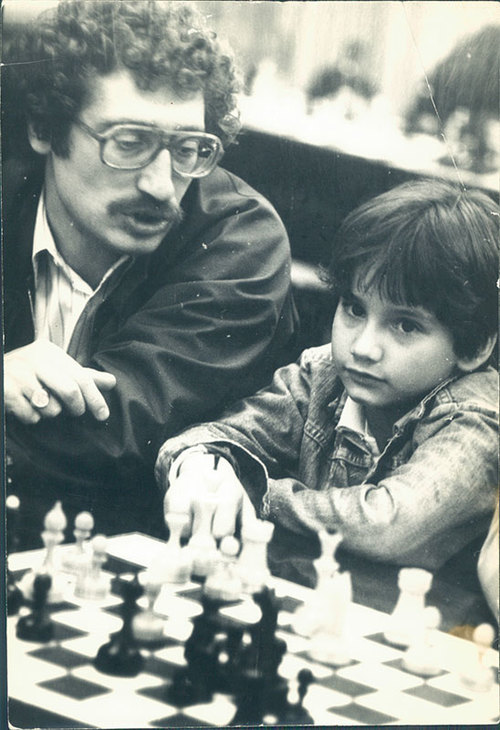

This made him capable of defeating seasoned adult players and even some chess masters due to his exceptional talent. His introduction to the game of chess happened at the age of six.

At that age, Josh while walking with his mother through Washington Square Park located in New York City saw a game of chess being played, probably among chess hustlers and it caught his attention. His plan that day was to play on monkey bars but seeing chess, he fell in love with it.

Josh started learning and playing with the chess hustlers out there, they were his first teachers. These park guys taught Josh their playing style — aggressive, crushing and intuitive style of playing. This became Josh’s trademark for years to come.

At 7, he began a classical study of the game with Bruce Pandolfini, an experienced and renowned American chess coach and author.

At 9, Waitzkin dominated the U.S scholastic chess scene by winning the National Primary championship in 1986, the National Junior High Championship in 1988 and the National Elementary Championship in 1989.

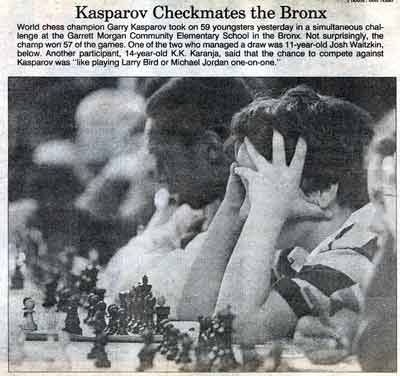

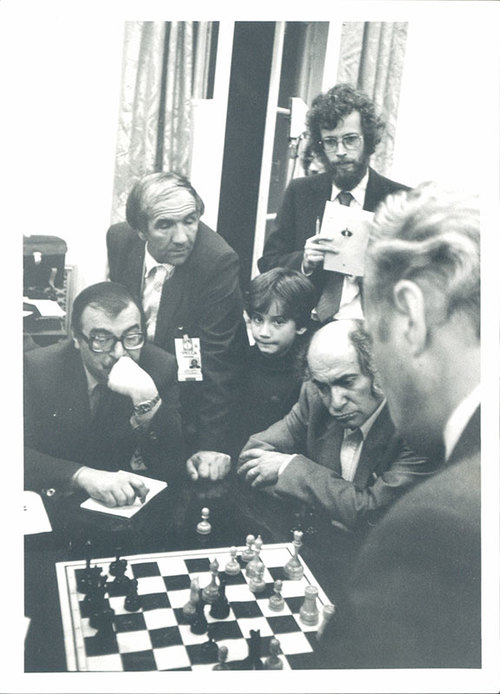

At about 11, He and fellow chess prodigy K. K. Karanja were the only two children to draw with World Champion Garry Kasparov in an exhibition event in which Kasparov played simultaneously against 59 children.

At 13, Waitzkin officially became a National Master. He emerged victorious in the National Junior High Championship for the second time in 1990, and also won the Senior High Championship in 1991, as well as the U.S. Cadet Championship (under-sixteen).

The young champ led New York City’s Dalton School to seven national team championships between the 3rd through 9th grades, in addition to his eight individual titles, during his time there.

At 16, Josh Waitzkin became an international master and the U.S. Junior (Under-21) Co-Champion. In that same year, Paramount Pictures released the popular movie “Searching For Bobby Fischer” based on a book by Josh’s father, Fred Waitzkin covering how Josh emerged victorious in his first National Championship.

At 17, he won the U.S. Junior Championship and placed fourth in the Under-18 World Championship in 1994.

The Beginning Of The End

…Brilliant creations are often born of small errors. – Josh Waitzkin

In 1997, Josh became the spokesperson and architect of the Josh Waitzkin Academy, for Chessmaster, the largest computer chess program in the world. He began his studies at Columbia University in 1999, where he majored in philosophy.

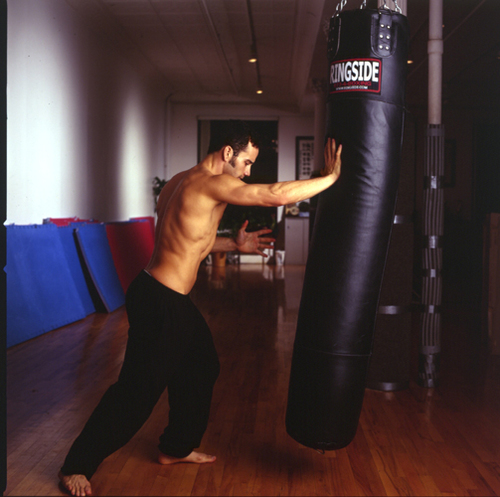

As a young adult, Josh’s attention shifted to the martial art Taiji. In this competitive sport, he earned multiple national medals and a world champion title from 2004.

Josh also became a championship coach, helping Grandmaster William C. C. Chen’s US Push Hands Team to multiple titles at the Tai Chi World Cup in Taiwan, including world titles for colleagues Jan Lucanus and Jan C. Childress.

Josh is also the co-founder of MGInAction.com and The Marcelo Garcia Academy, a New York City-based Brazilian jiu-jitsu school.

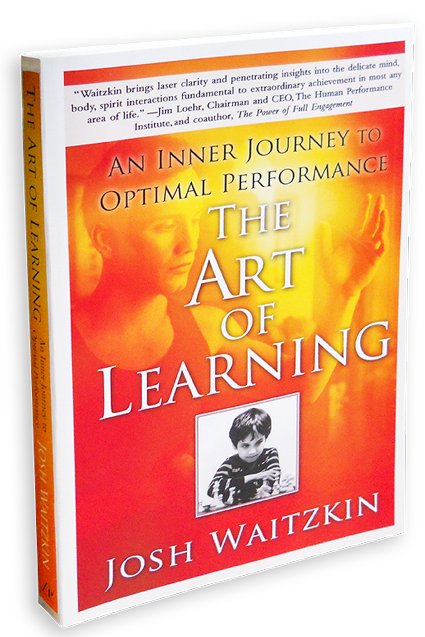

Waitzkin is the author of two books:

- Attacking Chess: Aggressive Strategies, Inside Moves from the United States Junior Chess Champion (1995)

- The Art of Learning: An Inner Journey to Optimal Performance (2008), an autobiographical discussion of the learning process and performance psychology based on Waitzkin’s experiences in both chess and martial arts.

Now the interesting part of the story comes to this — Waitzkin hasn’t competed in a US Chess Federation event and FIDE competition since 1999. His peak rating is 2480 which was obtained in July 1998.

This simply shows that he has not been playing since then. So why this? Down to our question:

Does Josh Waitzkin Still Play Chess?

As of now, Josh Waitzkin doesn’t engage in competitive chess anymore. He actually quit decades ago.

But why? In an interview, Waitzkin expressed his reasons for leaving chess:

“When people ask me why I stopped playing chess … I tend to say that I lost the love. And I guess if I were to be a little bit more true, I would say that I became separated from my love; I became alienated from chess somewhat … The need that I felt to win, to win, to win all the time, as opposed to the freedom to explore the art more and more deeply, and I think that started to move me away from the game and also chess for me was so intimate. It was something that I loved so deeply that when I started to become alienated from it, I couldn’t do it in an impure way.”

He also had some problems with his trainer, Mark Dvoretsky, popular Russian chess trainer and writer.

In his book, ‘The Art of Learning’, he made the following comments:

“In life, Dvorersky is a tall, heavyset man who wears thick glasses and rarely showers or changes his clothes. He is socially awkward and when not talking about or playing chess, he seems like a big fish flopping on sand.”

“During these periods, it seemed that every concern but chess was an intrusive irrelevance. When we were not studying, he would sit in his room, staring at chess positions on his computer.

At meals, he would mumble while dropping food on the floor, and in conversation thick saliva collected at the corners of his mouth and often shot out like streams of glue . If you have read Nabokov’s wonderful novel The Defense, about the eccentric chess genius Luzhin- well, that is Dvoretsky.”

“He is extremely confident, arrogant in fact. He is most at home across the table from a talented pupil, and immediately begins setting up enormously complex chess compositions for the student to solve. His repertoire of abstruse material seems limitless, and in keeps on coming hour after hour in relentless interrogation.

Dvorersky loves to watch gifted chess minds struggle with his problems. He basks in his power while young champions are slowly drained of their audacious creativity. As a student, I found these sessions to be resonant of Orwell’s prison scenes in 1984. where independently minded thinkers were ruthlessly broken down until all that was left was a shell of a person.”

“Mark Dvoretsky, on the other hand , has created a comprehensive training system that he believes all students should fit into. His method when working with a pupil is to break the student down rather brutally and then stuff him or her into the cookie-cutter mold of his training system. In my opinion this approach can have profoundly negative consequences for spirited young students.”

Josh Waitzkin

Some say his unfruitful relationship with Dvoretsky took away his love for chess and made it seem like a boring monotonous activity.

Some say that it was because of the massive fame he got after the release of the “Searching for Bobby Fischer” movie that made him quit, the pressure of being the next Bobby Fischer being something to deal with.

Dvoretsky on the other hand retaliated in his recent memoirs, “For Friends and Colleagues – Part 1″, dedicating a section to Waitzkin titled ‘The Fischer That Never Was”:

The title of the book and the movie, Searching for Bobby Fischer, is likely well-chosen in journalistic terms, but… We cannot know how our words will resound, wrote the great Russian poet Fyodor Tyutchev.

The title of the book echoed in a rather unexpected and, in my opinion, even somewhat tragic manner. Little Josh really began perceiving himself as an heir to Robert Fischer and believed in his enormous chess talent.

In actuality, he had decent chess abilities, but so did many others. For instance, Patrick Wolff or Tal Shaked have significantly brighter talents.”

“Josh’s mom, Bonnie, once wisely remarked that her son should not perceive himself as a character in a book but live his own life. Unfortunately, both the father and the son believed that Josh would follow in Fischer’s footsteps.

Unrealistic expectations gave rise to negative character traits and psychological issues. Hence, his jealousy towards other young chess players and his obsessive desire to constantly seek confirmation of his genius and his achievements.

The successes of his peers were perceived with much pain by the family. Once, I came to work with Josh shortly after a big Swiss tournament, the New York Open. Josh had a friend (indeed, the two families were close) named David Arnett, a capable, intelligent boy who played quite successfully at the tournament, especially at the beginning.

David loved chess, and I also gave him lessons. But still, for him, the game was just a hobby; he was interested in mathematics, and that is where he saw his future.

The Waitzkins feared that Arnett’s success in New York chess circles would outshine their own glory. And, when I arrived, the father and son separately explained to me that David had been getting lucky the entire tournament and did not deserve his good result. This shocked me because they were close friends.”

“The next day after the lesson, during which went over recent games played by Josh, I paid a visit to Alburt, and he stunned me: “You know, Fred Waitzkin came over. He is terribly alarmed.

He said that the lessons Dvoretsky is giving Josh are filled with an atmosphere of hatred! I tried to reassure him, of course. What happened between the two of you?” In fact, nothing happened; everything was quiet, no friction, no disagreements.

When I thought about this, I suddenly realized what was happening. Josh started by showing me how he drew Icelandic grandmaster Arnason with Black. It was a good, sound draw in the Richter-Rauzer Attack of the Sicilian Defense. Nothing extraordinary happened during the game.

We discussed it and moved on to the next one. But Josh certainly craved my admiration. Well, he had drawn a grandmaster with Black, is this not confirmation of his genius?! The fact that I did not pay much attention to his achievement was regarded by Waitzkin as a manifestation of my animosity, almost hatred, towards him. The Waitzkins very much wanted me to confirm that Josh was the best, the most talented.”

“Education is effective when it is interactive. During any of my classes, the students answer questions, solve puzzles, exercises, sometimes simple, sometimes quite difficult. For the vast majority, this is normal practice, and oftentimes a challenge that must be met honorably.

Such practice does not cause negative emotions but usually quite the contrary. But, for Josh, who identified himself with Bobby Fischer, any failure was a serious blow to his ego and his reputation. Since he had neither bright talent nor great diligence, his results were typically not too impressive.

Perhaps he really perceived the training process as very painful, as he was constantly tormented and suffering by inability to conform himself to his imagined level. I admit that it might have partially been my fault. I saw the inadequacy, the ugliness of his mentality, but I had no idea how far things had gone. I was hoping that I could get him back on track.”

“I remember that once I was staying for a few days at his home. I gave Josh an evening assignment, to solve a few relatively simple exercises. When we started our lesson the next day, it turned out that he had not completed the assignment. I asked him why.

After all, becoming a great chess player requires a great deal of work! Josh began explaining that he had a very busy schedule, difficult homework assignments in school, and that there was no time for anything. I said, “You’ve got to be kidding me! What does this have to do with school? I saw you quietly watching a basketball game on TV in the evening. You know, you have to choose one or the other.”

His school really was very strong, one of the best in New York. It was the one Morgan Pehme successfully graduated from. But Josh never did well there; his inability to work systematically was not exclusive to chess. In the end, he had to quit that school and finish his education at another, less demanding, school.”

Mark Dvoretsky

What do you think?

Check these out for a deeper dive into this topic:

2 comments

codeiherbdow

like this

Jeff Zoerner

I think, predictably, the truth lies somewhere in between. Really, from everything I’ve read, their versions aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive. Just a Rashomon thing.