Chess remains one of the oldest and most influential games in human history.

Aside from its strategic depth and symbolism, another intriguing aspect of the game is the movement of its pieces.

Each piece has a unique motion, one not designed randomly—it is a product of centuries of cultural, military, and intellectual evolution.

By understanding how and why the chess pieces move the way they do, we will come to appreciate the royal game more.

However, that requires us to take a quick glance at the game’s history.

We look at its ancient origins in India, through its movement and transformation to Persia and the Islamic world, before its final refinement in Medieval Europe.

Origins in India

The earliest known ancestor of Chess, Charuranga, emerged in India around the 6th century CE.

Nomenclature-wise, it translates to mean “four divisions of the military,” which were then composed of infantry, cavalry, elephants, and chariots.

Hence, the original piece’s movement was shaped by these divisions.

- Infantry (Pawn): Representing foot soldiers, their movement was slow. With just one step at a time, this is to symbolize their limited mobility but steady pace and presence.

- Cavalry (Knights): These are modeled after horse-mounted soldiers. Their L-shaped movement mirrors the unpredictable and agile nature of cavalry in real warfare.

- Elephants (Bishops): In Chaturanga, the elephant moved diagonally two squares at a time, reflecting the decisive yet cumbersome role of war elephants in ancient warfare.

- Chariots (Rooks): Chariots moved in straight lines across the battlefield just like today’s rook moves along files and ranks.

The King (Raja) and Counselor/Minister (later known as Queen) were key figures with limited mobility, requiring constant protection, symbolizing their crucial role in guidance rather than raw power.

Transformation in Persia and the Islamic World

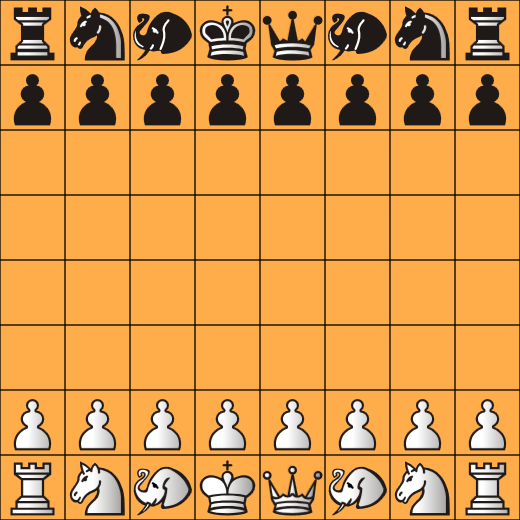

The starting position of Shatranj. Photo Credits: Pychess.org

When Charuranga spread to Persia through trading by merchants, it became known as Shatranj. The rules and movement evolved slightly:

- The Minister (Vizier), who would later become the Queen, was the weakest piece, moving just one square diagonally. This reflects the role of an advisor and Nobility rather than an active warrior.

- The Elephant (Alfil) kept its restricted diagonal movement, which mirrors the symbolic representation of Elephants in Persian warfare.

- Pawns still retained their slow, single square advance, emphasizing their indispensable role as soldiers.

Shatranj emphasized slow, strategic maneuvering, closer to a battle of attrition, in contrast to the dynamic chess we know today.

The European Influence and the Birth of Modern Chess

Paul Morphy playing Chess in the 1800s. Photo Credits: Chess.com.

By the late Middle Ages, when chess reached Europe, the game underwent numerous changes to make it faster and more exciting.

- The Queen: The change to the Queen is perhaps one of the most radical shifts to the game, as she gained her Modern power in the 15th century. Moving any number of squares in all directions. This was to reflect both the rise of mighty Queens in European politics (such as Isabella of Castile) and the desire for a more dynamic piece.

- Bishops: The Elephant’s limited leap was replaced with long diagonal movement, better fitting for the European interpretation of the Church’s influence spreading across the globe.

- Pawns: The introduction of the two-square first and special move, en passant, gave pawns greater flexibility, symbolizing the empowerment of the ordinary foot soldiers. Promotion (especially to the now-powerful Queen and other powerful pieces) further emphasized social and political mobility.

This, perhaps, is essentially what many historians call the “chess renaissance” turning the game from a slow war simulation into a dynamic intellectual war front.

Symbolism Behind the Movement of the Pieces

The starting modern chess position.

Each chess piece’s movement carries symbolic meanings:

- The King’s one-square movement symbolizes vulnerability and the need for constant protection. It is also the most essential piece in modern chess.

- Queen: The most powerful piece reflecting the politicking and advocacy nature of European Queens. This also mirrors the political shift in Europe, allowing for balanced gameplay.

- Rooks: Their straight-line motion resembles fortification (like a Castle) and siege weapons. This symbolizes stability and strength.

- Bishops: The diagonal movement mirrors the Church’s ability to influence indirectly rather than head-on.

- Knights: Their unusual and unique L-shape embodies unpredictability and creativity like a Knight on a horse. This makes them unique in the game.

- Pawns: They represent the average foot soldier’s slow advance and also symbolize the potential to rise through merit, promotion reflecting social aspiration.

Modern Chess and Its Legacy

The best players in the Modern age analyzing a Chess960 position. Photo: Lennart Ootes/Freestyle Chess.

Today’s chess remains a legacy and imprint of centuries of journey across different civilizations. The movements are not just arbitrary rules; they are historical narratives imbibed into the board.

Moving from the Indian battlefields of Chaturanga to the Royal courts in Europe, the movement we have come to know today is the product of cultural blending, symbolism, and the human desire to reflect realism in the Royal game.

Conclusion

Chess is not just a game of 64 squares and 32 pieces. The way each piece moves reflects centuries of military strategy, cultural imagination, and human history.

From the nimble pawn to the powerful and mighty queen, every move tells a story. It describes how society once saw war, power, and hierarchy. Understanding this historical context adds a new layer of depth to the game; every move on the board is not random. Strategy is a reenactment of history.

join the conversation